The WGA strike and the content-ization of writing

As WGA writers go on strike, it's time to ponder the consequences of labeling their work and everyone else's as "content."

Welcome to The Content Lab (née This Too Too Solid Flesh), a reader-supported publication about why it’s so bad to call everything “content.”

Today I’m talking about the Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) and its roots in the adoption of “content” as the demeaning conceptual framework for labeling and understanding seemingly all creative work.

Preface: I think the writers are in the right here and should have their demands met. Check out this post from The Present Age by Parker Molloy for more background on the issue at hand, and then join me after the jump.

2008 wasn’t so great

2008 was a year when decades happened. Beyond the Lehman Brothers meltdown and the Obama landslide, it was also the inflection point in the flattening of so much creative work into the category of “content”—the ubiquitous and dehumanizing term that has five main assumptions, all of which bode ill for labor and very well indeed for capital:

The container owner (whether that’s Netflix, Electronic Arts, or any centralized, attention-seeking social media platform) is the pivotal agent, not the person(s) filling up that container via their wage labor, for instance, at their WGA union job. “Content” centers such proprietary containers.

Anything from a blog post to a video series is essentially disposable—all of it just indeterminate “content” to stuff into that container and hope that people stumble through it while on their phones, something that isn’t viewed as a thing in itself but as a pure instrument, something to be checked off the list or used as grist for the hot-take mill.

Indeed, “second-screen content,” in those exact words, is what Big Content (the term I like to use for Netflix et al.) is aiming for from writers, per Michael Schulman for The New Yorker: The point isn’t to watch, but to post about it while watching it.

Algorithmic recommendation, rather than organic discovery, is the pivotal user journey; “content” is not something you choose, it’s chosen for you. The timelines of Facebook and Twitter, the categories on

HBOMax and especially the infinite feed of TikTok embody this logic.1All creative work has no value beyond the commercial activity it can drive. But because making it is so stressful and low-paying, and because the median work has so little chance of breaking through and generating profit in a low-margin industry, there has to be a ton of it to overwhelm the audience and make them feel FOMO to the point that they consume compulsively.

There aren’t any fresh ideas to capture the audience’s imagination, only old IP content mines and “Hero’s Journey” tropes to send creators down into. There are no new “texts as things in themselves,” to paraphrase Adam Kotsko, to be created and enjoyed on their terms—they have to be instrumentized, by being boiled down to SEO-optimized plot “analysis” (on sites such as The Ringer), SEO’d YouTube “5 moments you missed in [X]” explainers, and tedious debates about lore and canon. Check my full rundown of this assumption below, if you’re interested.

But what was so special about the year 2008 vis-a-vis this concept? Consider two events that bookended that year:

That winter, an WGA strike against the AMPTP that had begun in late 2007 ended. The strike had focused on issues such as DVD residuals and compensation for shows on streaming services. 2005-2009 was Peak DVD; disc sales were bigger than the box office. Meanwhile, streaming was still tiny. Netflix Watch Now (what we now just call “Netflix”) had launched in 2007 and been buoyed by its presence on the then-new Nintendo Wii. DVD and broadcast/cable residuals were enough for a sustainable life for writers, but the streaming ones soon wouldn’t turn out be.

In late 2008, the content mill (or more politely, “agency”) that I and my podcast cohost wrote for was founded. As Max Read put it in his Read Max, 2008 was the year when SEO got legs:

Marketers realized that publishing five 200-word blogs with titles like “The best managed cloud services for your small business” could exploit a loophole in Google News and direct a firehose of traffic to their company blogs2. Later this strategy evolved to incorporate Facebook shares, in the spirit of Upworthy-esque fare like “7 Things You Won’t Believe About Out-of-Band Management.”

The early 2008 WGA-AMPTP agreement provided writers with some shield against the then-upcoming dragon’s breath of commoditization, or “content”-ization, of their work as it transformed from permanent ownable items, such as DVDs, that generated substantial residuals, into perpetual digital services that generated far less of them. But now that shield has given in, and even unionized writers are really struggling against the ideology pioneered by those 2008-vintage content mills. Everywhere is becoming Content Mill Town.

Feeling so down in Content Mill Town

There are three main issues during the ongoing WGA strike that’ll be familiar to current and ex-content mill toilers alike:

More work, less pay

There’s an old shitpost tweet about a man flipping a quarter in a dark alley in 1925, fumbling it into a nearby sewer grate, and lamenting that he just lost the equivalent of $30,000. It’s sometimes referenced when talking about the declining rates for creative professionals, including freelance writers, who, as Malcolm Harris has documented, used to get the modern equivalent of $15 per word to write in print for the likes of William Randolph Hearst.

Celebrity writers were getting $1 per word back then; meanwhile, freelancers are lucky to get $0.40 per word today, despite all the inflation since Hearst’s era. This downturn leads to:

Writers needing to complete progressively greater volumes of work to survive.

Many of them ditching writing, especially if it falls to the left of center on the ideological spectrum, as a professional altogether, to instead tap into the right-wing money spigot or to work directly for Big Content or Big Social.

They’ve entered a profession having already lost at least one of those 1925 precious quarters—or rather having already had it taken away from them by people who don’t value writing as a craft.

Someone working at a place like the one in that footnoted Popula piece were expected to churn out thousands of words per day. If you calculate a rate per word based on volume and salary, you’d come to about $0.02. It was a pittance in the face of daily abundance—so many articles were going out every day, to in theory help organizations capture a downward trickle of Google’s multi-billion-dollar business, or to ride the tiger of Facebook referrals at the peak of Social Journalism, but writers themselves got almost nothing.

We were just there to fill up someone else’s (Google’s, Facebook’s) container, and we had to do it at a torrid pace or else we’d get fired. It’s no surprise that many content mill workers left over time for roles in PR, software, or any other sector that wasn’t expecting the volume equivalent of an Infinite Jest every 6 months.

WGA writers have likewise stagnated despite an explosion in “content” created by their labor against a backdrop of rising housing costs in places like Los Angeles. DVD and broadcast/cable residuals have dried up, and streaming ones haven’t replaced them. Work on “movies” and “shows” is now work on “original content,” and we shouldn’t gloss over that distinction—the public treatment of this work as “content” by the container owners has boxed-in writer compensation, while funneling almost all money to a smaller group of execs and shareholders.

Container owners see “content creators” (gross) as essentially box-checkers undeserving of even a rate or salary bump. Just as a manager in 2008 might’ve scolded a writer for failing to cram three keywords into the intro, a streaming executive today is going to chide them for not having some big set piece in the first 30 seconds, because that’s what The Data® says about when viewers tune out.

Content mill drudgery was relentlessly “data-driven” before it was popular to even use that phrase. Word counts, keyword placement, “dwell time”—it was a set of data inputs for a misery machine that prodded us to churn out individual articles that no one wanted to read that we weren’t proud to have written, and that could only catch anyone’s eye by being unavoidable in their unsightly volume. Who was all this for?

And now everything is so data-driven, either figuratively or, in the hopes of Big Content, literally (a chatbot churning out the worst thing you’ve ever read), so that human writers aren’t needed. I’m very skeptical of this “AI” position, but the very airing of it shows how “content” as a label is dehumanizing and designed to treat us like machines writing for a machine audience, as I explained in my best-performing (data-wise) post so far:

An uncomfortable and poorly-paying room

WGA writers have pointed to the issue of “mini rooms,” which involve small groups of writers working on shows and movies before they’re actually picked up/greenlit. This setup allows Big Content to pay writers much less for work that might not even air. Accordingly, they have to take on more gigs to make a comparable amount to what they would’ve gotten in a traditional writers’ room that had led to reliably residual-generating work.

Content mills don’t have writers’ room. Instead, some of them used to have mock newsrooms—long bullpen desks, lots of desk phones that no one ever had time to pick up while trying to hit their 4,000-word quota, and the overall appearance of “news” being generated amid the churning out of SEO sludge that might not ever get approved by the marketing manager at the other end.

Instead of a single reported feature that’d help sustain someone’s livelihood and give them visibility, we were writing multiple lengthy articles every single day, never getting a byline, and always needing to look for other gigs.

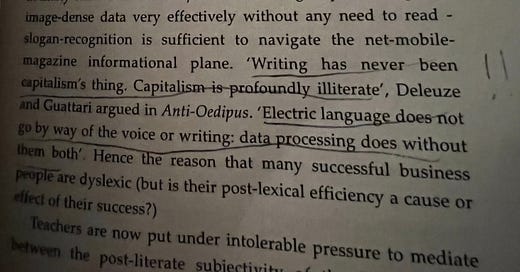

The room we did all this in was an everyday reminder of an Edenic fall from the days of relatively well-compensated newspaper jobs. We were in the same nominal “room,” but our work was both less valuable to our employers and more tedious to create due to the ambient pressure of having to do so much of it. We were living in data’s world, amid capitalism’s fundamental hostility to writing.

A declining industry being looted

It’s worth pondering that to The Extremely Offline (people who don’t, like, keep up with the Met Gala in real-time on Twitter, Bluesky, or Mastodon, or know who “@dril” is), text-centric websites might’ve just been a temporarily interesting phase in the transition from gossipy broadcast and cable TV shows to social video3. Indeed, the much-lampooned “pivot to video” that content mill employees got to experience firsthand in 2013-2014 may have failed to generate much traction for news-focused sites, but it was wildly successful in getting many of those places to either shut down or dramatically scale back their operations, by shifting money and eyeballs that might’ve gone to (often unionized) media shops over to non-union venues instead. Now people spend hours in TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube instead of reading articles or watching WGA-written shows.

Just last month, BuzzFeed News shut down. Vice is entering bankruptcy. The national freakout over TikTok has many causes, but one is that it’s swallowing up attention that would otherwise gone toward movies and TV shows. And it’s not the only thing competing for attention by industrializing non-union labor in the race for attention.

The famously union-hostile, “crunch”-loving video game industry is almost unrecognizable compared to where it was during the 2007-2008 WGA strike. Back then, there were zero iOS or iPadOS games, and the best-selling console was the gimmicky Wii, which for a supermajority of its owners was a way to play bowling for a few months in between streaming Netflix in standard-def. Now gaming is bigger than Hollywood and the music industry combined.

Streaming can’t match that, either for sustained attention or in sheer revenue. It just isn’t a very profitable business model. Just as it takes unfathomable numbers of Spotify streams to equal the revenue from one CD or LP sale, even one DVD sale can yield quite a bit more profit than a bunch of streams. Big Content tore down the proven theater-cable-DVD pipeline for something much shakier. Why?

Some of it was beyond their control, such as the downturn in theater revenue during the COVID-19 pandemic. But more broadly, streaming has won the race as “the future” not because it’s profitable but because it’s an end-around for the old highly unionized, less user-hostile (you can’t have your DVD de-listed from a platform on a whim) distribution model. It enables looting for the likes of David Zaslav, whose 2022 compensation alone would’ve been enough for the cumulative increases demanded by the striking WGA writers. Execs can see the industry struggling and they’re there to loot from labor amidst the chaos.

Zaslav says the strike will end because writers ultimately “love to work.” Whatever was keeping us toiling in Content Mill Town, it wasn’t our “love” of hitting word counts, stuffing keywords into question-laden sentences, or burning out trying to write a same-day 2,000-word summary of a live IBM event. We deserved the protections of a union, and so do the WGA writers. Solidarity.

The open-source social network Mastodon embodies the opposite logic—there are no algorithms or ads, and everything is served in reverse chronological order.

I can’t recommend enough the Popula classic “How to suck at business without really trying” for a great look not only at this strategy and the content mill industry in general, but at the workings of our content mill in particular.

This is why I’m so skeptical that anything can be “the next Twitter.” Twitter is an artifact of a bygone era and is popular solely because of the momentum it’s accumulated over 17 years.