“Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes is a massive novel—“overflowing with content,” as our modern-day SEO marketers would brand it, if it were brand (haha) new, and one that’s easy to imagine succeeding even if had debuted in 2022 instead of 1605.

Its episodic structure, mix of comedy and tragedy, and epic length would’ve made it perfect for social media and forums—similar to how video gamers have episodically chronicled the fine details of their progress through the similarly vast and challenging game “Elden Ring” on Twitter:

Likewise, imagine someone reading my hypothesized new-in-2022 “Don Quixote” and tweeting “Just got to the Knight of the White Moon and here’s a tip: It’s time to ‘reflect’ on the Knight of Mirrors passages from earlier.” It’s a fun book not only to read, but to tell others you’re reading.

This latter-day Don Quixote might even make it onto SEO lists alongside the likes of “Terraria” and “Morrowind” as works stuffed with content, although based on Google search results it’d probably be a better fit for “first modern novel.” (“Modern” is such a slippery word that, yes, I think someone could write a 1,000 word blog—maybe “Why ‘Don Quixote’ is the first modern novel for the post-‘Euphoria’ world”—if “Don Quixote” were newly published in 2022, and rank highly for it in Google).

For a work in Spanish, “Don Quixote” has had lasting influence on English:

The saying “the proof is in the pudding,” though it has origins in Middle English, is sometimes linked to Pierre Motteux’s loose 1700 English translation of Cervantes’ “al freír de los huevos lo verá1.”

William Shakespeare, the foremost content creator in the English language, based a lost play, “Cardenio,” on a “Don Quixote” episode.

“Quixotic” is derived from Don Quixote’s name.

An early episode in which Don Quixote jousts with some windmills he thinks are giants is the source of “tilting at windmills.”

The last one is Don Quixote’s most memorable imprint on English. To tilt at a windmill is to fight an imaginary foe with your lance at full tilt. You’re not just attacking a shadow, you’re going all out while doing so.

I’ve thought of this idiom more often ever since immersing myself in the world of content mills, whose name seems to denote a different type of “mill”—a factory, basically—but still shares some essential qualities with the windmills of Cervantes’ novel, namely the incredible hold they have on the minds of content creators, and the illusory nature of what anyone actually gets from engaging with them.

What are content mills?

A content mill is a factory for content—what I’ve defined as “work that must work,” any type of writing, music, video, or other creative output that can be:

produced quickly

easily digitized, if it isn’t already digitally native

crammed into someone else’s container (whether a website, streaming service, or other publication)

shown off in hopes of gaining audience engagement; SEO2 is critical for this purpose

monetized, with much of the benefit flowing to the container owner, not the content creator

talked about after-the-fact as an inanimate object that nevertheless “engages” and “attracts” actual people, primarily through the software that distributes and measures it, as well as through the algorithms to which it appeals.

Content mills industrialize the content creation process. That means content mills are all about volume, just as a factory farm is all about producing as much pork, milk, or (insert any agricultural commodity here) as possible. Factory farm operators often push right up against the limits of any applicable regulation, and likewise content mill owners aim to churn an inhuman amount of material out of their content creators.

I follow an American Prospect editor and podcaster named Ryan Cooper on Twitter. He recently published a book, “How Are You Going To Pay For That?,” whose writing process he chronicled in real time:

Word counts are abstract to most people—how long is 1,000 words, really—but let me chime in and say that 2,500 words in one day is wild. Someone writing at this pace would produce something as long as Shakespeare’s greatest piece of content, “Hamlet” (29,551 words) in just 12 days.

It’s also in the neighborhood of the volume content mill employees are expected to produce every single day.

Content mills usually have a mix of full-time staff and freelancers. Industrial content creation at these organizations requires so much work that it may be one one of the few types of employment better done freelance than full-time.

A freelancer is someone whose lance is not sworn to any lord—someone who can joust with any content mill they want to. Typically, the freedom of freelancing is illusory—rates are lousy, payments slow, and workloads volatile—but such is the grind and obligation of dedicated content milling—a job I’ll refer to from hereon as that of a “content miller”—that even freelance chaos may be preferable to content mill predictability.

Life in the content mill

Content mills, like content itself, are a quintessentially 2000s construct, molded by the combined forces of economic inequality, a slack labor market, and the dominance of streaming as a result of growing broadband adoption. There emerged in those years a huge reserve army3 of talented writers, photographers, videographers, musicians, and so on, many of them with multiple degrees, who couldn’t find sustainable work—that is, getting paid a Carrie Bradshaw-esque rate4 for an article, or getting a major cut of a $20 CD sale instead of a fraction of a penny from Spotify, wasn’t in the offing—and had to turn to either the long odds of becoming a breakout content creator or taking on multiple jobs.

Demanding higher pay for difficult work such as writing an informative blog post wasn’t practical, either, because of the sheer number of desperate unemployed and underemployed people (Engels’ “army,” as described in the footnote) who could’ve been brought on to do the same work instead. Conditions were prime for institutions that could sling low-paying but steady assignments at creators. Enter the content mill.

Early content mills were built for the world of blogs and Google News. A writer working in such a mill might have a workday that included:

Walk into a trendy open floor plan office with an exposed brick décor and open up a list of assignments, each one assigned a value based on its length and complexity (for example, a 400-word blog might have a value of 2, whereas a 200 word would have one of 1). Circa 2008-2013, most of the assignments would’ve been short, 200 words typically.

Set a target for the day, based on adding up those values. Let’s say a combined value of 20, equal to 4,000 words.

Realize that even this nominally easy task of churning out a bunch of very short blogs was actually unbelievably daunting, even if you had the ability to let quality slide.

Do all research on Google, because who has time to interview anyone when you’re writing one-seventh the length of “Hamlet” every day.

Recycle press releases, often quoting the same people they did.

For more technical topics such as private cloud vs. public cloud, try to throw in just the right mix of words to sound knowledgeable, despite being a novice.

Eventually see your own hastily published articles cannibalize the search results you’d been mining for information.

In turn, scouring forums for more nuanced knowledge that hadn’t been optimized for the SEO machine.

Hit your target on the first day or two when you still had the high of having a new seemingly stable job, but then lose your ability over time as burnout sets in.

See a triple-digit paycheck hit your bank account and wonder what the point of anything is.

This particular workflow, with lots of mini blogs, began to collapse as social media hit the stratosphere in the early 2010s. Short-form, link-heavy, and RSS-dependent blogs declined in popularity, and so did the appetite for the content mill fare that clumsily imitated it5. Content mills couldn’t sell a pirate’s chest full of “Cloud computing networks foment growth of data center infrastructure going in to 2015” posts to naive small businesses anymore in the world of Twitter, Instagram, and influencer marketing.

For content millers, this pivot didn’t make life any easier, though. They had to instead produce a similar scale of work, only this time in the form of longer white papers and blog posts, to get ranked highly by Google’s algorithms, newly focused as it was on nebulous “quality.”

But the same question remains across these transitions: Why have content mill employees consistently needed to produce content at such incredible scale?

The expectation is that a dedicated content miller, to an even greater degree than a freelancer or self-employed content creator, will be what Jes Skolnik has perfectly labeled an “endless content spigot.” With that expectation comes an implied sacrifice of any sentimentality about what’s being created. Indeed, as a content miller, you likely won’t receive any direct credit for your work, and your job is only as secure as your physical endurance, because you need the stamina of a young person to type out the literally millions of words you may end up writing, sleep, and pick yourself back up to do it all again the next day. You’re expected to be a machine.

Humans in the machine world: hypercapitalism’s effects on the content lifecycle

The answer to this “why so much?” question lies in how content sellers—such as content mills, who sell content to businesses—conceive of content creation.

In the inaugural edition of this newsletter, I riffed on how people speak of content creation as something removed from human agency:

Consider the adjective that so often modifies content: “compelling.” This word denotes a strong, driving force, and yet it so often is used to impart those traits to inanimate blog posts and illustrations—content in its various forms. There is compelling content, but no compelling creators.

Similarly, the top result for “content mill” in DuckDuckGo includes the telling phrase “Because content is what makes the web go round.” In this conception, content, not people, is what powers the web, which itself is portrayed as an animate object (“go round”).

In short: Content sellers see content as something mechanical, primarily produced and consumed by machines.

Said “machines” are increasingly literal on both the production and consumption sides:

Production: Every day for at least as long as I worked in the content mill sector (nearly a decade) there was some new story similar to “This AI writing app creates killer content automatically,” about how AI was getting really good at churning out content. In reality, AI isn’t very good at anything language related6, but its preeminence in the American imagination helps to devalue the craft of writing, by reducing it to a set of digital inputs (enjoy my pun on the meaning of “digital” as “fingers”?). Human writers are expected to behave like machines—to work quickly and predictably, without complaint or pushback (no unionization for sure).

Consumption: Who reads SEO articles? Arguably, the most important reader is not a person, but a machine, one whose inner workings “we” (as in, non-Google employees) never fully understand. Articles are written and endlessly optimized with data on keywords, audience, and so on, spread across numerous tools, to rank for an opaque algorithm. This paradox is often overlooked. In his book “Capital and Ideology,” Thomas Piketty talks about how one of the core characteristics of our current age of hypercapitalism7 is that despite the enormous advances of information technology, we still have very little transparency into or data on how capital is accumulated and how much of it its owners really have. The Google algorithm is a microcosm of this trend: A proprietary black box that makes lots of money in a data-heavy world, but resists compete understanding or mastery by outsiders.

The mechanical nature of Google has made its results lower-quality. SEO spam, much of it from content mills, overwhelms it, crowding out the organic blog posts that might’ve ranked on page one years ago. AI-driven posts attract an AI (that is, Google itself, the machine behind all the searches) audience.

The robot-to-robot discourse doesn’t help anyone except Google and content mills. Writers enslaved by the machine8 create low-quality content mill fare for a machine to absorb. Trying to find something informative often requires resorting to the public knowledge on forums such as Reddit that hasn’t been put through the full SEO Rube Goldberg machine, but which Google still needs as a failsafe for actually answering your human question.

This blog post neatly ties together the SEO and AI threads to explain why Google has become worse:

Google increasingly does not give you the results for what you typed in. It tries to be “smart” and figure out what you “really meant”, in addition to personalizing things for you. If you really meant exactly what you typed, then all bets are off.

Google’s years-long decline has only made content mill life worse, by forcing content millers to write awkward, keyword-stuffed content with lots of questions as headers (even this newsletter isn’t immune, as you may have noticed) at massive scale for a non-human audience, for non-human wages. Content millers really are tilting at windmills—their audience isn’t who they typically think it is. Don Quixote imagined giants in place of a real windmills, and content millers imagine human readers where there are actually just machines.

And the relationship with Google is adversarial, just as Don Quixote’s was with his imagined giants: The content miller has to overcome something—Google’s AI-infested algorithm—that they can’t fully see or know.

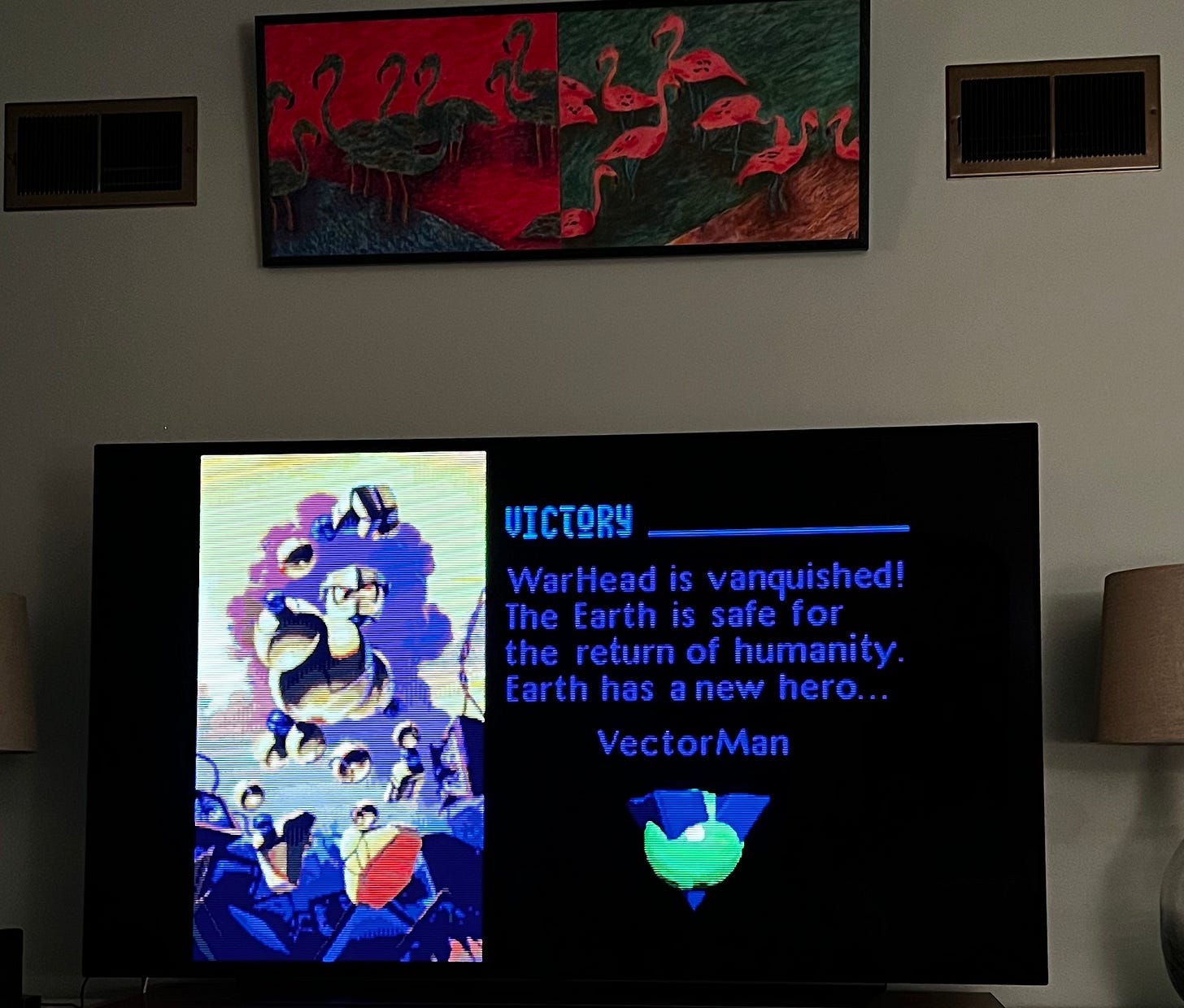

It’s a dismal reality, similar to the world of the Sega Genesis classic “Vectorman.” The game’s prescient plot involves an Earth abandoned by humans, who’ve left it to colonize other worlds. “Orbots” stay behind to clean up the pollution9 and monitor these efforts via a planetary surveillance network. It’s all robots, all the way down, similar to how content mills and Google are like two machines engaged in a dance.

But at least Vectorman had a happy ending—the eponymous character eventually helps make Earth safe for humans to return—so perhaps there is a way out of the content mill machinery, too.

Thanks, 15 Things You Might Not Know About Don Quixote, a great example of a mid-2010s SEO post.

And by “SEO,” I mostly mean “appeasing Google’s opaque algorithms.”

Friedrich Engels coined this term to refer to how capitalism creates structural unemployment, with a mass of workers whose ranks swell and diminish based on booms and busts in the business cycle. By continually attempting to squeeze more labor out of fewer workers, capitalists help ensure that some number of people are always desperately looking for employment and thereby putting downward pressure on wages.

People wrongly think RSS died with Google Reader’s demise in 2013. RSS is alive and well as the key protocol behind podcast distribution. It’s also a great way to consume the handful of good blogs left, via clients such as NetNewsWire.

Please read this long, detailed blog about why you should be less impressed by AI than you are.

This term is an English translation of the French original. Piketty is not a Marxist, but the English term has some history in Marxist discourse.

This evocative phrase is from “The Communist Manifesto.”

“Recycle it, don’t trash it” was a ubiquitous message on arcade screens around this time