Content: The emergence of a hazardous concept

How "content" ran roughshod over its human creators

Welcome to This Too Too Solid Flesh1, a newsletter about “content,” the industries that have sprung up around it (most notably, “content marketing”), and how promoters of the concept—people who use the word “content” as propaganda to describe corporate strategy and/or creative imperatives—ultimately erode any notions of human agency while working “content creators” to exhaustion.

Writers, photographers, videographers, musicians, and other artists are often said to create vast amounts of content—digitized things grouped together, despite their obvious differences in form and unique individual associations for both their creators and consumers.

But at the same time, content is also creating its creators, branding them as common cattle in a content seller’s herd and disciplining them into a burnout-bound regimen as they chase attention.2 One has no choice but to create content. At least for now. This newsletter, from a content skeptic and ex-content marketer like myself, is testament enough. And creating that content is costly, to the creator, if not the one(s) commissioning and/or platforming the work.

Rebecca Jennings chronicled the toll content takes on its creators for Vox, tracing the advent of the “creator” label back to late 2011, when YouTube acquired Next New Networks. Calling someone a “YouTube [content] creator,” instead of a “YouTube star” (the previous dominant lingo) had the advantage of being both utilitarian and vague. A “creator” could be anyone, doing humble tasks, if they just worked hard enough—at least in theory. In practice, the typical content creation experience is as draining as any job, without any guarantees of validation or remuneration, as one creator told Jennings:

Not a second goes by that I’m not thinking about creating content. I don’t watch sunsets or have genuine moments with my friends without being like, ‘Can we do that again? I wasn’t recording.’” He said that being a content creator for most people doesn’t become profitable for a year and a half, if that. “Every day I ask myself, did I really choose freedom, or just a fancier cage?

This snippet from an obscure essay on music3 likewise underscores how content demands everything from its the creator while returning so little:

free and excessive content

But what is content, anyway?

As a word, “content” is impossible to avoid using if you work in any industry from marketing to video editing. Undoubtedly, it’s a versatile term, and it seems harmless—what could blander than a word that may as well be interchangeable “stuff”?

I admit I initially struggled to define “content” as I wrote this newsletter, until I came across this tweet from Doomscrolling Reminder Bot creator Karen K. Ho, about the movie Turning Red:

Content is work. More specifically, it’s digitally native work that maintains the mystique and immateriality of digital things, while exerting tangible, analog pressure on its creator. The best metaphor for it is perhaps an evil digital-to-analog converter4, converting abstract and grandiose notions of online domination into physical sensations, in this case, almost-certain pain for the content creator and potentially pleasure for the content consumer.

It’s nothing as innocuous as “stuff.”

We may call something a “newsletter,” “song,” or “show,” but to the person signing the praises of “content” or, more materially, signing the paychecks, it’s all “content.” It’s designed to fill up a container—for example, a /news or /blog section of a website, or the bonus track section of a “digital deluxe edition” album—hit a production quota, or create another monetizable presence. Content is a broad term that blurs the distinctions between a vast array of human skills, from writer to illustrator—it’s all the same to the person(s) demanding the creation of content, so long as it works.

Content is work that must work. It has to connect with an audience, it has to sizzle, it has to be compelling. Note how “content” itself is the agent in these constructions, performing extraordinarily animated, human-like actions for enraptured audiences, while the creators themselves are less visible and more isolated. This content-as-prime-mover notion is especially evident in the seemingly redundant term “content marketing.”

What is content marketing? This answer from Oracle doesn’t get us much further than telling us that content marketing is marketing, but driven by that muse/god/demon, content:

Content marketing is the process of creating and distributing digital assets, such as blog posts, videos, ebooks, technical and solution briefs, and a variety of other digital content to provide information to your audience.

Content marketing is essential to search engine optimization (SEO) success. To rank at the top of online search results, you need to create engaging, high-quality, in-depth content related to your industry, business, and message.

As a former content marketer, my spin on this jargon is that, whereas marketing by itself is mostly about ideas and plans, content marketing is about work—utilitarian work that can be done by any person (“you”), across any format (“a variety of other digital content”), under pressure "(“essential…you need”), to prostrate before some idealized, romanticized, and almost godlike form (“engaging, high-quality, in-depth”). Content marketing connects the analog domain of people painfully churning out content with the digital one of pontificating about the wonders of content. And there’s obvious tension between the work quality expected by content evangelists and the grunting conditions of the creators doing the work.

To add to the pressure, those evangelists require evidence of that work, more so than ever in the content marketing context. That content is tracked with a precision that would make Frederick Winslow Taylor5 blush. Marketing analytics, KPIs, customer-expected ROI: Whether a creator works solo or as part of a content mill/content marketing firm, they’re on the clock and being watched.

Ultimately, to orient a business around the imperatives of content is to force creators to create anything (“digital assets”—the implied possibilities are endless) that can, under ideal circumstances, navigate the ever-shifting tides of search, social media, and other online communications channels to grab someone’s attention. It demands flexibility from creators, who are expected to master multiple forms, with complete deference to niche consumer preference and opaque algorithms.

This article from RIS News captures this ideology underpinning contemporary content marketing:

Creating digital experiences that cut through the noise is tough for retailers. Many more businesses, prompted by the pandemic, are creating additional e-commerce channels to generate sales. At the same time, shopper expectations have escalated. This has created a much greater need for digital content that helps shoppers make better choices about the products they want—at the time they want them…

Retailers should consider a lean approach to content production, which involves limiting the number of jobs in progress, where each is completed before the team moves to another. With this tactic, retailers can get this done much faster, in hours not weeks.

There’s mystical-sounding vagueness here—“digital experiences”—plus some software/automation adjacent language around being “agile” and “lean,” the centering of the nebulous yet omnipotent consumer, and the all-important time imperative (“hours, not weeks”). Content creators are expected to bend themselves into any shape6 to maximize productivity and either boost the company bottom line (if they’re employed by a content firm) or increase their own odds of hitting the audience lottery (if they’re going solo). One day, that prime directive may mean writing a longwinded newsletter, another, fashioning an NFT giveaway. Either way, everything has to be done quickly.

So content has no native form—the entire concept is one of adaptable work that the creator must accept. Circa 2008, the prevailing content form was short blog posts, often with recycled press release details, that could help businesses rank in Google News. Then Google’s Panda update mooted that approach.

“Quality content,” meaning longer-form but not necessarily more coherent or useful writing, became king. When I came into the content field at the dawn of the Panda era, I quickly learned that even the most elegantly written, pseudo-academic treatise was just grist for the content mill—something the author didn’t own and that existed solely to serve a fickle audience at the receiving end of a vast machine.

Like its vintage 2008 predecessors, it, too, was also customer-centric, SEO-bound, and caught up in meaningless platitudes, as in this quintessential LinkedIn article, which advises “putting in time and effort to generate unique content for your company [emphasis mine] and “[producing] beneficial content.”

Beneficial—but for whom? The person or the machine?

A word caught between capital and labor

Exploring the total benefits of content, and how they’re distributed, requires going back to the word itself. Content is a perplexing keyword, denoting a bounded container (its Latin root means “things contained”) yet also connoting the boundless expanse and perceived opportunity of the online world. Which meaning is more important to you depends on your relationship to the production of the content work.

The content seller

Some people sell content in a managerial capacity. Content sellers include:

Marketers

“Gurus”

Company executives

To this group, it’s the boundless expanse meaning that’s vital. “Content is king,” you might’ve heard, one of the hoariest of all marketing cliches, employed to emphasize the role of content in attracting and converting leads from across every channel, but especially online.

The “king” lingo brings to my mind the cover illustration of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, with a giant monarch composed of the individual bodies of the citizenry. Content is like a sovereign ruling over the body-politic, with unlimited resources to command the economic relations it wants. The phrase actually originated with Bill Gates, who wrote in 1996:

[The internet] allows material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience. The Internet also allows information to be distributed worldwide at basically zero marginal cost to the publisher. Opportunities are remarkable, and many companies are laying plans to create content for the Internet.

Content here is infinite, formless. The mechanical “internet,” not a person, is the protagonist. Among the numerous things Gates classifies as content are “not just software and news, but also games, entertainment, sports programming, directories, classified advertising, and on-line communities devoted to major interests.” Content is everything in this formulation. Calling it “king” really is Hobbesian, in how doing so creates something huge and uniform out of everyone’s unique bodies. The individual colors of writing, painting, you name it, have become the gray sludge of almighty “content.”

The content seller is peddling a wild vision, of conversions, of engagement, of riches, ultimately. This vision doesn’t align with the rote and poorly remunerated tasks required of the content creator. Gates’ essay lowers the expectations for content providers being paid and likens their work to the menial task of operating a photocopier.

The content creator

For a content creator such as a writer or musician, it’s that original etymological container aspect of content that’s most pressing. How do I fill up (to literalize things a bit) this word count, hit this quota, and keep my engagement up, day after day?

Whereas content is continuous for its sellers, it’s discrete for its creators, who go about filling up these defined containers for others. There’s the illusion of control and independence, but the platform (YouTube, Spotify, Google, et al.) rules. Creators are definitely not the main guy on the cover of Leviathan; they’re the citizens he lords over. They’re meant to be utilitarian.

That aforementioned phrase “free and excessive content” really pulls at the mixed implications of content for creators. Its author identifies the decline of fixed-capacity formats such as the audio CD and the concurrent rise of MP3s as catalysts of a push from record labels for artists to add lots of extra content to their albums, but at no extra charge, despite the immense labor required.

So content means boundless opportunity for the labels and for content sellers more generally, and it means bounded work—“units” of it, “content calendars” stuffed with it, “deliverables” packed with it, and all of it tightly bounded in its compensation, too!—for everyone else. It’s “free” for sellers, insofar as they can pay bottom dollar for it and distribute for zero marginal cost, and “excessive” both in its reach and in the strain it places on creators.

Speaking from experience, even professional, salaried content creators, much less most freelancers and people venturing out on their own, can’t escape these tangible pressures of the content machine. Because marginal distribution cost is zero, there’s always the demand for more. Volume is the real Leviathan/king of content.7

The content consumer

For the content consumer, content is both continuous and discrete. Its continuous aspect is evident in the seemingly infinite choice of shows available to binge, tracks to stream, and so on, while its discrete aspect is apparent in various anxieties about getting through specific batches of content—a coping mechanism for sorting the undiffentiated mass denoted by “content.” Can I finish this whole series tonight? What if they’re something else I could be consuming right now? After all, there is “free and excessive content” everywhere I look.

These complex anxieties are pushed onto the content creator, who must bear and interpret them. No wonder “we” do crazy things like try to take super controversial positions (“hot takes”) to boost subscriptions.

A history of content

Content as a concept hasn’t always been with us, though. Specific decisions stitched it together, and others could unravel it. Its rise wasn’t inevitable.

In an interview with Vulture, Chuck Klosterman argued that the 1990s were the last decade with a distinctive culture attached to it. I disagree, and my overall rationale is beyond the scope of this post, but I’ll make one specific point, relevant to this piece, in rebuttal: Content is a quintessentially 2000s concept, shaped by these historical circumstances:

The 2008 Lehman Brothers meltdown and all of the responses to it, including the wave of home foreclosures. This sequence of events created a vast reserve army of desperate humanities major with content-creating skills, who were a perfect match for nascent, low-paying content mills specializing in the relentless production of SEO content.

The wealth inequality that further stratified American society into an elite of content sellers, and a lower rung of content creators, a few of whom are successful and the rest of whom burn out trying to create enough content to survive. The former group seeds the dream that success is possible and that putting up with the content grind is somehow worth it.

Downstream effects such as the disintegration of individually bought and own items (such as CDs, DVDs, and boxed video games) that once returned decent sums to their creators, and their replacement by streaming services, on which everything is just bits on a network and compensation is much stingier. The ideal metaphor here is a utility—something that makes money in a utilarian way:

Content took form during a major recession, and it shows.

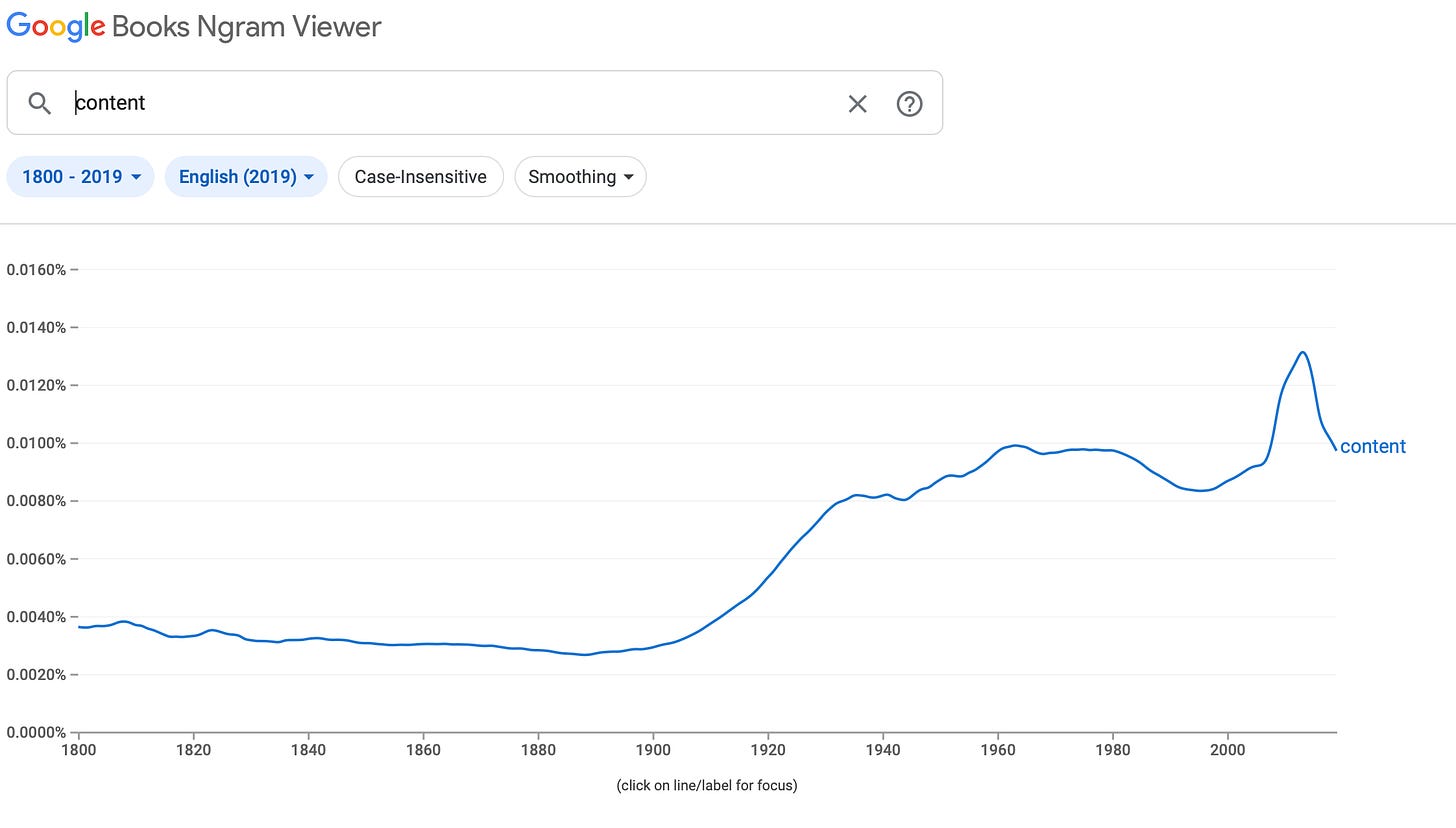

There’s also a related, longer-running historical trend of monopolization and the embrace of hypercapitalism8 in the 21st century U.S. economy, which created bigger firms who designated the all-encompassing concept of content as their purview. Fittingly, content as a word only achieved widespread popularity in the 2000s, following some more modest growth in the late 20th century:

The 2000 AOL-Time Warner merger was a watershed moment along this trajectory.

Dialing into AOL-Time Warner

The March 2, 2000 U.S. Senate hearing on The AOL-Time Warner deal showed politicians and C-suite execs exploring the contradictory meanings of content as something simultaneously boundless and bounded. One senator mentions the “treasure trove of content” at Time Warner and the universe of “video, music, and print content that pervades America’s everyday life.” Here we get content in the sense of something omnipresent and inescapable—godlike.

Later, another senator broaches the issue of content discrimination, due to content production and its delivery falling into the hands of a single firm. The idea of content being slowed down or simply blocked by a vertically integrated provider-distributor, for instance on the grounds that it came from an unaffiliated creator or didn’t fit into some strategic vision, reminds us that content is still a bounded, discrete thing, with distinct characteristics and ideologies branded on it by its creator(s).

Today, content is still this something discrete, that anyone can theoretically make, distribute, and get rich from, but its status as a continuous and exploitative moneymaking scheme for content sellers—those AOL-Time Warners and content mills—dims this prospect. Far from being egalitarian, the entire industry has become intertwined with the reactionary self-help space, with key players such as The Content Marketing Institute addressing its blog posts directly to the reader (“you may be missing out on a key part of a successful content strategy”) and providing circular tips (you can apparently “create great blog titles” if you just “focus on titles”), but which have an Everyman DIY audience. The idea that content is something anyone can do is inherent in both the lenient, Great Recession-informed hiring practices of content mills, and in the ways in which what Vox calls the “creator economy” can feel like a multi-level marketing (MLM) scheme, another reactionary sector of the economy—open to anyone willing to try, but seldom rewarding.

So content continues to have two fundamentally opposing meanings: Bounded and labored-over, boundless and effortless.

You can get lost in endless SEO articles promising to streamline the discrete and bothersome actions of content creation—researching, scheduling, business planning, and so on—and remind us of the labor involved in content. This is the multi-level marketing (MLM) dimension of content. Grunt work is expected, but in the end, there’s just a handful of winners and most everyone else fails to find an audience. They put in the work anyway, because what choice is there?

Meanwhile, content is also something that, well, continuously pervades society, as the senator puts it, and seems to exist beyond human agency. There’s “persistent, decentralized, collaborative, interoperable digital content” coming in the metaverse, apparently. In this sense, content is something we can’t stop or control; the capital that drives it through marketing channels does what it wants, and to it, content is ideally almost costless and effortless, despite obvious evidence to the contrary.

The ways in which content both obscures the creator and also brings them uncomfortably to mind, highlighting the contradictions of the industrialized creative process, makes it hazardous. I use this word in reference to Leo Marx’s essay Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept .

Why content is hazardous

Marx’s essay focuses on how “technology” as a term emerged to fill what had previously been “a semantic void” that had confronted anyone trying to comment on the rapid development of scientific knowledge and its industrial applications in the 19th and 20th centuries.

People used to say we were entering the age of the “machine,” but that term turned out to be too blue-collar and dirty to elevate the study of those innovations to the same rarified level as the fine arts. Marx says:

Whereas the term mechanic (or industrial, or practical) arts calls to mind men with soiled hands tinkering at workbenches, technology conjures clean, well-educated, white male technicians in control booths watch- ing dials, instrument panels, or computer monitors. Whereas the mechanic arts belong to the mundane world of work, physicality, and practicality— of humdrum handicrafts and artisanal skills—technology belongs on the higher social and intellectual plane of book learning, scientific research, and the university. This dispassionate word, with its synthetic patina, its lack of a physical or sensory referent, its aura of sanitized, bloodless—in- deed, disembodied—cerebration and precision, has eased the induction of what had been the mechanic arts—now practiced by engineers—into the precincts of the finer arts and higher learning.

He also notes the congruence between technology and corporate capitalism, a relationship borne from the latter’s creation of profit-making private enterprises built upon specialized knowledge, for instance, of railroads. “Technology” is undoubtedly the “sanitized, bloodless” propaganda that Marx says it is, and so is “content.”

That’s because the term hides the differentiated human labor necessary to create it, much of which corresponds to roles—writer, painter, musician—that aren’t considered “good” careers anymore. In its place, content evangelists substitute a vast system of synthetic relationships that govern the complete range of workmanlike tasks (recall how Jennings focuses on “creator” being utilitarian jargon) of writing, drawing, recording, and so on, applying to all of them a common logic of mechanically getting something out there, to harvest ad dollars, drive subscriptions, and generally “boost engagement.”

Content evangelists love to talk about robotic concepts like “content optimization,” strongly dependent on marketing automation software, that feel and are far removed from direct creativity and differentiated effort. Companies specializing in content per se even have slogans such as “Marketing is impossible without great content,” a phrase that centers the goal of content and connects two inanimate ideas—marketing and content—but not the means by which they’re created. And sure enough, an actual software vendor in this space highlights the central problem of “I have a content marketing plan, but it’s not engaging my customers,” underscoring how content and the abstract concepts that adjoin it (“engagement,” in this case), are the agent. The human content creators on their teams, and/or on the teams of their clients, are often lowly compensated and nearly anonymous, with few or no bylines or ownership of their work. These humans become secondary.

Marx saw the same thing happening in the construction of technology as a concept. He concludes by warning about the tendency “to invest the concept of technology with agency,” because doing so erases humans as causal agents. Today, the same con happens with content.

Consider the adjective that so often modifies content: “compelling.” This word denotes a strong, driving force, and yet it so often is used to impart those traits to inanimate blog posts and illustrations—content in its various forms. There is compelling content, but no compelling creators.

For Marx, there was a disconnect between what technology evangelists considered the true automotive “system”—basically, just the internal combustion engine itself!— and all the other parts of the related industry with human faces, such as the engineers, dealers, and repairmen who obviously sustained that tech, but who were still cordoned-off and deemed part of “the rest of the society and culture.” In content, there’s a similar “engine” that’s preeminent for evangelists—engagement, compelling-ness, the software tools that track, optimize for, and monetize these concepts—and then there’s the world of creators, editors, mentors, site reliability engineers, and many more who contribute directly and indirectly to content (Marx likewise goes on a tangent about all the related personnel who keep the auto industry humming). Content is in the end human motion, even when it’s presented as something software-driven and mechanical.

To stay on theme, I’ll wrap up with one of Hobbes’ most famous lines, about how motion is the essence of life. Let’s remember that behind every content creator is a person, putting their body and mind into their work and often seeing that effort contorted into the inhuman buzzword of “content.”

Life is but a motion of limbs. For what is the heart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body, such as was intended by the Artificer?9

The reference is to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, 1.2.129-159. In that soliloquy, Hamlet wishes that his “too too solid flesh” would “resolve into a dew.” I like how Shakespeare explores the durability of the body despite its inhabitant’s desire for it to become incorporeal. That tension makes me think of how so much of the digital content space—streaming, blogs, and so on—is made to seem similarly incorporeal, almost spiritual, divorced from physical reality. But of course it isn’t. It still requires living, breathing humans to create and maintain it, and physical artifacts such as vinyl records and books persist, reminding us that a different world was and is possible.

I say this as someone who has written millions of unbylined words for money.

I’m not sharing the title, where to find it, or any other details, out of respect to the author’s wishes.

DACs convert numbers into voltages and pressures to make audio audible.

John Pat Leary has written a fantastic post about “flexibility” as a keyword of capitalism.

This article is too good at describing volume-driven pressures in the content industry.

I’m lifting this term from Thomas Piketty’s fantastic Capital and Ideology.

Leviathan, English edition.